Rio De Janeiro’s Olympic Legacy: Public Security for Whom?

| Lea Rekow 1 , 2 |

| 1 Arts, Education & Law Group, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia |

| 2 2 Green My Favela, 59 Franklin St, suite 303, New York, NY 20013, USA |

* Corresponding author. |

1.- Introduction

Even before the World Cup and Olympic bids were secured, the state government of Rio de Janeiro began to recraft its image as a safe and glamorous mega-events wonderland. In order to satisfy the International Olympic Committee, the city focused on overturning the city's reputation for violence—and violent policing—especially inside its urban favelas, made up of a assortment of informal and irregular settlements, occupations of abandoned buildings, and substandard government housing complexes that together weave a loose fabric over Brazil's second largest mega-city. A “Games Security Plan”, devised by the state and put into operation by all of Brazil's three government levels (federal, state and municipal)—was launched as one of the greatest legacies of the Olympics [1]. It was implemented in two divisions: the “Public Security Integrated Regions” for the asfalto (formal city); and the “Police Pacification Units” (UPP) in the favelas.

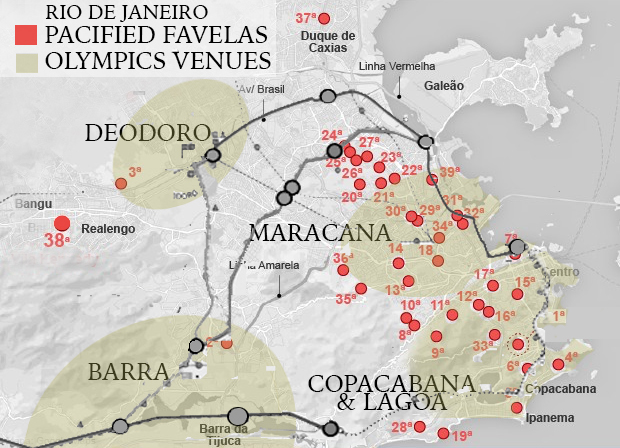

Rio's police pacification campaign officially launched in 2008. Since that time, 38 of Rio's 763 favelas have been occupied by a range of Rio's Special Ops troops and military police including the UPP police, BOPE (Elite Special Operations Batallion troops), Choque (Shock troops), and CORE (Civilian Police Special Resources police). To date, 9,543 UPP officers [2] have been installed in efforts to `pacify' those favelas in proximity to mega-events venues and tourist areas throughout the city. With one or two exceptions, all UPPs are located in areas crucial to the commodification of the city—that is, the hosting of mega-sporting events, athletes villages, tourist facilities, important traffic and transportation routes, and Games headquarters (Figure 1).

The priority of the UPP is to take control of designated favelas that are informally governed by armed drug gangs and corrupt ex-forces militias. The concept was sold using terms such as 'community policing' and `sustainable security', and promoted as being concerned with providing human security [3], however pacification relies almost exclusively on traditional military force to achieve the state's geopolitical goals of controlling territory, people, and resources. As a result, the people in Rio's favelas are subjected to many forms of politically engineered violence.

Figure 1. Map of Rio de Janeiro showing pacified favelas in relation to Olympic venues, tourist sites, and major transportation routes.

As a military offensive, pacification serves multiple ends. It utilizes a range of police forces to ensure that many of the goals of the government's rapid urbanization agenda—Rio's greater Olympic Legacy—are met. This urbanization agenda theoretically encompasses the social component of pacification, that is, to provide favela residents with the public and social services and infrastructure necessary to elevate their citizenry rights. However, Rio's pacification has come to be exposed as little more than the military facilitation of David Harvey's concept of “accumulation by dispossession” [4], justified by the `war on drugs' [5].

From the beginning, the pacification policy has been supported by a heavily funded media campaign. Following the winning of the Olympic bid, Rio's marketing budget underwent substantial growth. From 2006 to 2009 the municipality’s annual expenditure on advertising, marketing and media increased from R$100,000 to R$ 800,000. After Mayor Eduardo Paes took office in 2009, the marketing budget jumped to R$ 29 million (for 2010), and by 2015 it had reached a staggering R$127 million [6]. Much of it has been used for the marketing of pacification in relation to the Olympics. However, as the Games draw closer, the appeal of military pacification has worn thin, and the cracks that have always been present in the policy have widened into gaping fissures. The police were responsible for one in five homicides in the city during 2015, and the rates continue to escalate during the final count down to the Olympics. Not even Rio’s marketing campaign, championed by Brazil's right-wing media conglomerate [7], can keep spinning a positive story.

There are many aspects to pacification, far too great for the scope of this paper to cover [8]. Even within the policing framework of pacification, there are too many moving parts to discuss within this context [9]. Therefore, this paper aims to provide a background understanding of pacification policy in relation to the context of military ‘policing’ and how and why policing tactics have evolved to play out on the ground as the Games draw near [10]. Its intent is to impart a broad understanding of how pacification policy functions for those living in pacified favelas, and outlines how public security policy and the Games Plan in general, is affecting the city as a whole.

To this end, this paper describes how UPP and other Special Ops forces are operating in favelas, and how other military deployments are being positioned so that they can be deployed more broadly across the city for the Olympics. It discusses what impact these operations are having on favela residents and their right to the city, particularly as it relates to their personal security. In this context, the residents' right to the city is determined not only by the right to access to public space and resources, but freedom of mobility, and the collective right to be involved in how their favela neighborhoods are being shaped through policing.

2.- Scope & Method

This paper begins by providing a brief historical context that lays the groundwork for examining the city's pacification framework and urbanization-related public security initiatives connected to the 2016 Olympic Games. It then examines how the police are operating on the ground inside the favelas and outlines issues of militarization and police violence and how this ties to Olympic urbanization activities and a political and judicial framework that serves Rio's elite public officials and large private interest groups. It explores the socio-economic cost of the Olympic fallout, and lastly offers policy considerations for understanding the difficulties in limiting Rio's political landscape of corruption and violence.

The information has been derived from qualitative fieldwork conducted by the author in five of Rio's north and south zone favelas and favela complexes between the years 2010 and 2016. It tries to describe key dimensions that have impacted on pacification policing policy and procedures undertaken to effect public security conditions inside favelas. These conditions are subject to rapidly-evolving sets of precarious and fragile policy variables that render it impossible to measure the real-time impact of public security policy as it plays out in the lives of everyday people during the Olympic Games. Its aim is, therefore, to provide a general overview of how pacification operates, how it is linked to urbanization activities, how residents are being affected within the pacification scenario, and how the city has been affected by the Olympics, and the policing and criminal justice policies that surround it.

The author has used a mixed methodology approach based on multi-year qualitative research that has been cross-analyzed against a range of empirical data. Qualitative information was derived from direct observations, conversations with favela residents, meetings with citizens' committees and Residents’ Associations, interactions with drug traffickers, UPP officers, government urbanization workers, and municipal stakeholders. Empirical research has included an examination of articles of law, statistical data [11], municipal and state development plans, architectural design documents, human rights reports, and mainstream and independent media reportage. Participation in conferences, meetings, and reviews of literature produced by other researchers [5] engaged in analyses of Rio's mega-events and urbanization activities also provide a foundation with which to check and balance the paper.

3.- Historic Backdrop

Rio's favelas began to develop toward the end of the nineteenth century as the country abolished slavery and transformed from a Portuguese empire into a Republic. As informal settlements grew, urbanized, and became more heavily populated, residents organized internally to form associations and create the basic infrastructure that the government had failed to extend to their communities, such as channels for sewerage, transportation systems, roads, informal real estate title exchanges, and commercial enterprises. State [12] abandonment, sporadic government-led military police incursions, forced population removals, and the slow takeover of territory by drug trafficking gangs, however, has progressively limited residents' access to public security, spatial mobility, social infrastructure, and earning capacity beyond any kind of subsistence existence [13].

Rio has always been characterized by a great divide between wealth and poverty, and in recent years the income gap has begun to increase even more, making it one of the most unequal cities in the country [14]. The favelas are estimated to house more than 1.4 million people, or 27% of the city's population [15]. 20.7% of the city live in households with a per capita income of less than half the minimum wage, roughly equivalent to US$ 6 a day [1]. Existing on half of that, 9.2% of the population survives on less than a quarter of the Brazilian minimum wage—earning just US$ 3 a day. In pacified favelas, the poverty rate is even higher—with a third of the population (34.5%) earning less than US$ 6 per day, and almost 1 in 8 households (12.8%) existing on less than US$ 3 per capita a day [14]. In general, the opportunity to earn a living wage is low at best, and out of reach for the overwhelming majority.

The 1980s brought new power bases, struggles, and economic opportunity to Rio through the US-led `war on drugs'. The city was transformed into a principal point for the international transit of cocaine and a large domestic market in itself, and the favelas—where State presence was never well established—became ideal territories from which drug trafficking gangs could operate. Over time, the scaling-up of the drug trade (that before had been limited to local residents dealing small quantities of home-grown marijuana) to traffic large quantities of cocaine, gradually resulted in absolute gang control over many of the city's favelas.

As cocaine replaced marijuana at the bocas (drug sales points), drug networks and power relations began to change. A new generation of heavily armed young foot soldiers governed by “micro-level warlords” [16] created a system of governance whereby teenage boys patrolled the streets with everything from AK-47s to Goliath rocket launchers. These youths bear resemblance to child soldiers in that they operate within armed factions with military-grade weapons inside a command structure that controls territory, people, and resources [17]. However, they are also interwoven into the fabric of the favelas through familial ties.

The dangers presented by gang culture, as well as turf battles between any combination of gangs, police, and militias (gangs of corrupt police and prison guards who operate as guns-for-hire), have continued to place residents in the crosshairs of armed conflict. These conflicts closely resemble other global security situations that are formally defined by International Humanitarian Law as `non-international internal armed conflicts' [18] that, at times (and especially at this current moment) bear a notable resemble to war zones [1, 19]. In the favelas, the impact of these conflicts is strikingly evident. Almost one in five people have had a family member fall victim to homicide, and levels of youth homicide are estimated to be seven times that of the rest of the city [88].

The drug trade has clearly destroyed autonomous agency and brought much harm to the favelas. However, the State’s institutionalized culture of extreme police brutality has also taken a heavy toll on favela residents. Rio’s many notorious police forces have consistently been criticized for their blatant disregard of human rights. Following the formation of BOPE in the early 1990s, conflict between the drug gangs and the police rapidly escalated. BOPE troops were incentivized by policies such as the `Wild West gratuity', implemented from 1995–1998, which increased a police officer's monthly salary according to how many 'criminals' an officer killed. The policy was credited with a drastic spike in the number of extra-judicial killings at the hands of the police during this era, a trend that increased over the years to reach its height in 2007 when there were a recorded 1,330 killings across the city at the hands of Rio's police forces.

At this time, the federal government launched the National Program for Public Security and Citizenship (Pronasci) to tackle the country's public security problems in preparation for a series of mega-sporting events, including the Pan American Games (2007), the FIFA World Cup (2014) and the Olympics (2016). Rio de Janeiro was prioritized as a funding recipient to receive a large portion of the US$ 2.12 billion pledged to be invested over a five year period in collaborative actions coordinated by states and municipalities [1, 21]. The program aimed to carry out a set of interdisciplinary joint crime prevention operations which were to be designed with the “participation [of] the community” through programs “aimed at improving public safety” [22]. Thus, the military pacification campaign was born.

The Pronasci funds allocated to finance the UPP were dramatically strengthened by the government’s largest private sector partner, the EBX Group, owned by businessman Eike Batista, who between 2011 and 2013 invested R$ 20 million per year (more than US$ 25 million in total) in UPP security equipment, vehicles and technologies [2]. Batista's financing of the UPP program was almost five times higher than the government funding allocated to the military pacification units. By the end of 2013, however, both EBX and Batista's oil conglomerate OGX [23] had filed for bankruptcy [24], and Batista had become the target of a federal investigation by Brazilian regulators. Batista's withdrawal from the UPP partnership in 2013, the phasing out of Pronasci funding around the same time, and Brazil's deteriorating economy, has collectively dealt the campaign a huge financial blow [25]. Yet despite the mounting economic challenges, the campaign—for the time being—continues to hold.

4.- The UPP Framework

The legal existence of the UPP is based on a very lean regulatory framework consisting of just a few decrees [26]. The criteria for selecting locations for pacification, as laid out in legal text, are poor communities with a low institutional presence and a high degree of informality, and where armed criminal groups affront State democratic law. The three main objectives of the UPP are:

-

a) to consolidate state control over communities under strong influence of openly armed crime;

-

b) to return local people to a state of peace and public tranquility that is necessary for the exercise of full citizenship, and that guarantees development in both social and economic terms; and

-

c) to apply timely, effective and plural instruments—with emphasis on mediation—to resolve events related to conflict [26].

Corresponding social objectives, some of which are outlined in law, and others which have been publically stated, include the installation of public services; the expansion of the private sector; the regularization of land holdings; rapid urbanization and the growth of economic development activity; and the integration of pacified territories and their inhabitants into the formal city. There are also objectives that are deliberately avoided. These include a) ending drug trafficking; and b) winning the war against crime [27].

With the UPP focused on retaking territory, the State's narrative has changed from ending drug trafficking to the disarmament of traffickers [28]. Thus, even though the UPP has been promoted in connection with the ‘war on drugs,’ it has shifted the public security debate to distinguish its mission as a territorial issue, rather than one of eradicating the city’s drug-trafficking economy [29].

The pacification process has followed four basic sequential steps:

-

a) Tactical intervention—initiated by Special Operations military squads (BOPE and Shock Troops)—to establish territorial control;

-

b) Stabilization—through Special Ops siege actions;

-

c) Installation of specially assigned UPP troops;

-

d) Evaluation and monitoring by the Rio+Social program [1], which occurs after `stabilization' has been achieved [26].

Military pacification occurs through a massive coordinated military invasion of the favela—by BOPE, Choque, CORE, and a range of armed forces and other police divisions. This is followed by a BOPE occupation of the favela, which after a time transitions from control to UPP units, with Special Ops troops continuing to patrol and assist in operations when required (Figure 2).

Figure 2. UPP patrol, Manguinhos favela, 2013.

The pacification process is normally accompanied by Choque de Ordems (Shock Orders) that shut down various forms of informality [30]—by relocating or removing residents; by closing unlicensed businesses; by outlawing particular forms of cultural events such as baile funks (funk dance parties); and by imposing curfews. These orders are enforced by Special Ops troops and UPP officers who, until March 2016, continued to benefit from a modified version of the Wild West policy, which has been reinvented, amended and applied under a different name [31]. Up until this time, UPP officers received financial compensation of up to R$ 9,000 (US$ 2,830) annually if they met their 'crime reduction targets' in the favelas [32]. This increase augmented an officer's salary by as much as an additional 80%. Approximately R$ 200 million (US$ 63 million) of the R$ 1.8 billion (US$ 0.57 billion) invested by the municipality in pacification since 2008 was specifically spent on salary bonuses for UPP police who met their target goals [33]. In April 2013 alone, almost 12,000 of Rio's police officers and public servants received financial bonuses for meeting their target goals [34].

Yet, the low base wages that Rio's PM officers earn—R$ 906 a month (2014), or approximately US$ 250—have posed a critical problem in relation to corruption [35, 36] and made police an easy mark for traffickers. Many have been accused of supplementing their incomes by working with gangs to supply illegal weapons, to run drugs, or to provide protection [13]. Frequently referred to as state-sponsored killing, murder or death squads, pacification troops are estimated to take seven years off the average life expectancy of residents in Rio's favelas [37].

5.- A Landscape of Aggression

According to the official narrative, the process of pacification brings peace and freedom to the residents of favelas [38]. Yet the police are regularly charged with taking bribes from traffickers [39], of bribing witnesses [40], and of other forms of extortion [41] and corruption [42]. Moreover, they are charged with high levels of ongoing human rights violations, including rape, murder, torture, and ill-treatment of detainees [34].

Those who are poor, young, and of African-Brazilian descent are particularly vulnerable to falling victim to lethal violence perpetrated by police, organized crime, or death squads. A UN Committee on the Rights of the Child report issued in 2015, voiced alarm at the lethal violence carried out by the Military Police, the UPP, and BOPE against children in favelas during Shock Order operations aimed at cleansing the city in relation to mega-events, including the Olympics [43].

The UN Committee is deeply disturbed not only by the extraordinarily high number of extra-judicial executions of children by military police, militias, and civilian police, but by a range of other violations of children’s rights. These violations include torture and disappearances of children during military and other operations by security forces, particularly in favelas; physical violence against children, including the disproportionate use of tear gas and pepper spray during forced evictions for urban infrastructure projects and/or the construction of mega-event venues for sporting events; the arbitrary arrests of children on the basis of combating organized crime; physical violence in police cars; the denial of access to legal assistance and medical care; physical violence during body searching; and sexual harassment of girls during pacification operations [43].

A 2016 study commissioned by the committee and conducted by sociologist Julio Waiselfisz claims Brazil ranks 3rd place for child homicides (out of 85 countries analyzed). In other words, 29 children per day are murdered in Brazil (2013) [44]. Alarmingly, a 2010–2012 study by Waiselfisz also reveals that, on average, youth murders by firearms are 285% higher than for the rest of the population, meaning that for every four children or teenagers killed by gun violence, only one person from the rest of the population died the same way [45].

There is also widespread judicial impunity afforded to the police for their actions. The state prosecutor's office dismisses 99.2% of incidences of death involving police—even when evidence directly contradicts the police version of events, points to the use of excessive force, or is a clear cut case of unlawful killing [46]. This makes clear why people living in Rio's favelas are more scared of the police than they are of either militias or drug trafficking gangs [47].

Another troubling statistic reveals that during Sérgio Cabral's reign as Rio's governor (2006-2014), nearly 40,000 people were documented as disappeared or missing (a rise of 32%) [48]. This figure correlates to the drop in homicide rates during the same time period. And though homicide rates fell in favelas during the initial years of pacification [27, 49], between 2006–2011 the number of violent non-lethal incidents soared—from 29.4 to 99 per 100,000 inhabitants. By 2014, reported incidences of rape and domestic violence (previously outlawed under gang rule [50]) had tripled under the UPP [27, 51].

Outside of the favelas, the story of rising crime was much the same. Between 2012 and 2013, pedestrian robberies surged more than 32%, vehicle thefts rose 46.7%, assaults on buses jumped 118.4%, and cargo theft soared by 175.6% [52]. By the end of 2014, muggings (which have been steadily increasing over the last decade) were up by more than 42% [53].

Since 2012, lethal violence has also risen substantially. The city's homicide rate in Rio's poorer North Zone in neighborhoods such as Baixada Fluminense rose by 28% between January 2012 and September 2013. In the nearby commuter city of Niterói, homicides rose by 27% due to criminal gangs relocating after being forced out of pacified favelas [54]. The number of people killed by Rio security forces between 2013 and 2014 spiked by 40% [55], there was a 69% increase in extra-judicial resistance killings by police throughout the state, and a 77% increase in the city. Overall, homicides in Rio were up more than 18% statewide for January 2014 [52] (compared to the previous year), with a 4.3% rise in the city itself [56]. From January through October 2014, 481 people were killed by the military police in Rio, a hundred more than during the same period for 2013 [46]. And between 2013 and 2015, homicides resulting from police intervention in the state of Rio de Janeiro increased by 54%. To put it a different way, on an annual basis, the police in Rio have been killing about the same amount of people as do the entire police forces of the United States [57]. Most are poor, between the ages of 15 and 29, and black. Nationwide, 77% of all homicide victims fall into this demographic [58].

In addition, pacification has dramatically increased the number of favelas in which criminal militias operate in—from six in 2004 to 148 in 2014. Militias have now spread beyond the city to control 195 communities in 23 of the 90 municipalities throughout the state [59]. In January 2015, armed confrontations between militias and traffickers accounted for 80% of the 130 homicides that took place in Baixada Fluminense [60].

Stray bullets also present a growing problem (Figure 3). There were 111 people hit by stray bullets in Rio in 2013. And in the first month of 2015, stray bullets injured 32 people [61] and caused five deaths throughout the metropolitan area, including those of women, young children, and adolescents [62]. A 2014 UN paper based on 2009–2013 statistics revealed that Brazil has the second highest number of stray bullet incidents in Latin America (behind Venezuela) [63]. Rio's Security Secretary José Beltrame has attributed the majority of stray bullet shootings to “bandits' attachment to guns” [62] though anthropologist and former BOPE officer Paulo Storani, claims that it is more likely that a large portion of the stray bullet problem is attributable to the pacification's displacement of drug traffickers [64] to unpacified areas. This leads to attempted territorial takeovers of these areas which are governed by rival gangs.

By 2016, the security situation in Rio's favelas had started to spiral out of control. According to Amnesty International (AI), during the first quarter of 2016, homicides resulting from police interventions in the city of Rio de Janeiro increased by 10% compared to the same period in 2015, by mid-2016 lethal police violence had increased by almost 80%. In the first three weeks of April alone, at least eleven of the city's favela residents died in this manner [65]. By the end of the month, the number had reached 78 statewide [66]. And civilians are not the only casualties. In the first six months of 2016, 71 UPP officers were shot in pacified favelas, thirteen fatally (Figure 4) [67].

Figure 3. Spent shell casings collected from the ground after a police shooting in the Manguinhos favela, 2015.

Figure 4. UPP unit headquarters in Manguinhos, fortified with cement barricades.

Having heavily armed and violent drug gangs govern inner-city neighborhoods is clearly an untenable security situation, and no doubt some benefits have come from public security interventions under the UPP. However, the single most positive claim associated with life under UPP was that residents would be more able to walk around the favelas more freely without being subject to armed violence [1]. Yet, social gathering spaces, whether indoors (for example, cultural venues including children's theaters) or outdoors (for example, community gardens, parks or football fields) have become indiscriminate shooting galleries for police. People are not even safe from being shot while having lunch inside their homes. Military operations have shut down schools, kindergartens, health clinics, businesses, and access to favelas. Being involved in protests against the tens of thousands of forced evictions that have preceded the Games also presents a risk to personal safety. A large majority of residents now feel unable to move around their neighborhoods without fear of being shot by police [68].

6.- The Violence of the Games and the Judicial Framework That Supports It

Since the announcement of the Olympics in 2009 through to mid-2016, 2,500 people have been killed by police in Rio [69]. Ask a mother in a favela how many children she has, and she's likely to answer, “I have X number of children, Y are still living”. Although the escalation in police killings cannot be directly linked to the Olympic preparations, these numbers do connect Rio's public security forces to an escalation in the use of excessive violent force ahead of the Games. AI fears that “the risk of increased [rights] violations committed directly as a result of hosting the Olympic Games is great” and that these violations may occur without appropriate investigation or prosecution, as has been the case in the past [70], especially during mega-events such as the World Cup, when police killed 580 people in the state of Rio de Janeiro, a 40% increase than in the previous year. The number in 2015 was even greater—645 dead, most uninvestigated [71].

Due to Brazil's economic free fall, Rio's State Security Secretary Beltrame, announced at the end of the first quarter of 2016 that Rio's R$ 7 billion state security budget was to be cut by about 35% for the year (a reduction of R$ 18 billion)—effective immediately [68]. As a result, the Games plan to utilize approximately 65,000 police and 20,000 military troops for Olympic security (the largest security operation in Brazil’s history) [72] has been thrown into disarray. The public security forces that were to be commandeered from other states—now also in crisis—have been significantly reduced [73] because of the strain on state coffers, some of which have fallen to as low as US$ 10,000 [74]. Adding to the crisis, several of Rio's state civil police divisions' salaries have been withheld since March due to a lack of available funds [75]. For the moment, UPP salaries are being continued through a special funding donation from Rio's State Legislative Assembly (Alerj), however the UPP crime reduction target bonuses have been discontinued [76]. These laws are also expected to contribute to the risk of rights violations.

In an effort to stem ongoing public discontent around these issues, an array of bills and laws have been introduced to crack down on almost any form of freedom of public expression, especially around mega-events [7]. In 2013, just months ahead of the World Cup, the Ministry of Defense issued the Guarantee of Law and Order (GLO) [77]—a set of guidelines allowing wider discretionary use of the military for law and order operations and to quash public protests without transparency or accountability monitoring mechanisms. The decree outlined an “operational plan” for “disorder control in the urban environment”, and included any social movement or opposition to “undermine public order”. The GLO also aimed to craft the “flow of information to the general public, especially the media” [7].

The approval of yet another federal Anti-Terrorism Act (Law Project 2016/2015), passed this time just months before the Olympics, further criminalized the already strict legal lockdown on exercising the right of freedom of assembly. The law defines terrorism as the practice, by one or more people, of sabotage, violence, or potentially violent acts, “when committed with the goal of causing social or generalized terror, or exposing people, public patrimony or authority to danger” [78]. The deliberately vague language used to define terrorism allows for any form of social protest to be punished with up to a 30-year prison term. The Act is expected to result in a further increase in unchecked police violence during the Olympics, especially those that occur in the favelas. Rafael Custódio, coordinator of Justiça da Conectas, states that on the eve of the Games, the government “approved the Project on an emergency basis, without any discussion with society, [as] an instrument to criminalize collective protests movements”. Moreover, he claims that “the legacy of the Olympics for Brazil will be the weakening of [its] democracy” [79].

Going even further, in May, the Federal Government signed the “General Law of the Olympics” [80] to impose heavier restrictions upon the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly in Rio. Essentially the new GLO is an even more repressive reissue of the General Law of the World Cup. AI calls it a failure by Brazilian authorities “to deliver the promised Olympic legacy of a safe country for all [or] to ensure that law enforcement officials meet international law and standards on the use of force and firearms” [81]. Pacification is part of this framework. They are the enforcers for what social researchers Brito and Oliveira call “the transformation of Rio de Janeiro into a large tropical theme park” [82].

Military police are on the frontlines of the violent and forced evictions that have driven at least 67,000 favela residents from their homes [83] all over the city to make way for Olympic facilities, transit routes, and tourist sites. The police execution of Shock Orders, which shut down informal businesses [84], typically follow, further undermining the already low chances that the city's poorer residents have of achieving socio-economic stability [85]. None of this comes as a surprise. As David Zirin has made clear, “so much of the Olympics historically has been about displacement and the repossession of land for the wealthy at the expense of the poor” [86].

José Roberto Bassul asserts that in Brazil, State resources and investments have always benefited the private sector by adopting urban planning regulations that privilege Brazil's real estate and construction sector giants, and moreover, that urbanism has long been characterized by the private appropriation of public investments and the segregation of large population groups who are excluded from access to essential services, and who reside in favelas and substandard government housing complexes. Thus, the social struggles for the right to the city have traditionally been linked to structural urban reform [87], and the military police have systematically been used as the primary means by which the public's freedom of expression, and people's right to life, have been suppressed.

7.- Into Debt: The Calamitous Fall of the Olympic City

Numerous urban reform projects have gutted the city's poorest neighborhoods in service of the Olympics. James Freeman discusses these at length in his paper “Neoliberal Accumulation Strategies and the visible hand of Police Pacification in Rio de Janeiro” (2012). Freeman links police pacification to the violence of Rio's entrepreneurial activities centered around developing the city as a mega-events venue—a strategy which he sees as a clear cut case of accumulation by dispossession. He describes it as the state engineering of “military conquest and control of territories, and the capture of assets by force to create outlets for the expansion of private capital” [89]. Rio's mega-events have caused so much civil unrest due to these processes, at enormous public cost, that they haven't even been able to provide the `feel good factor' of civic pride that normally accompanies them [90].

It has been estimated that the Olympics may cost Brazil as much as 0.7% of its GDP. The US$ 11.1 billion in estimated costs (including more than a US$ 1 billion in security) may eventually reach as much as US$ 16 billion. For Brazil as a whole, the economic returns are dismal. The event is expected to result in overall gains of less than 0.2% of GDP, and no more than 12,000 in employment opportunities. The IOC, which owns the majority of broadcasting rights for the Games, is the largest revenue earner, accounting for almost 50% of total profit from the event.

As was the experience with the 2014 World Cup, the Olympics have turned out to be much costlier than anticipated. Massive cost overruns for 'Olympic legacy projects' include exorbitant infrastructure spending, more-expensive-than-envisaged sports venues, and cumbersome security logistics. In June, the IOC had to advance partial payment of the US$ 1,045 billion due in August to stave off Rio's cash deficit. A cash shortfall of R$ 19 billion in Rio's state accounts has resulted in indefinite delays in pension payments to retirees; thousands of government employee salaries being withheld, including those of police, teachers and hospital workers; 70 schools being `occupied' by students; the State University on strike; and dozens of emergency health units and hospitals being closed because of a lack of medicines and equipment.

The budget shortfall is in large part due to a dip in the collection of VAT and oil royalties. According to the State Court of Auditors, Rio granted R$ 138 billion in tax relief between 2008 and 2013, much of which went to the private construction and real estate development giants that received the Olympic contracts. This led to the state’s tax exemptions exceeding the amount of taxes collected. As a result, in June, just seven weeks before the Games, Rio's acting Governer Francisco Dornelles declared a “state of public calamity”, pleading for emergency funds in order for the state to “honor commitments to the Olympics”. This paved the way for Brazil’s Interim President Michel Temer to inject R$ 2.9 billion in emergency funds into Rio for use in expenses relating to the public safety of the Games. Sources at the Rio Olympic Committee have confided that R$ 1 billion will be spent just on the opening ceremony. State Representative Marcelo Freixo calls the decree “unconstitutional” [91].

The city's Olympic facilities contracts were bid on by only one consortium—the Rio Mais syndicate—which consists of Latin America's largest construction and engineering giant, Odebrecht [92] (whose former CEO is serving a nineteen year prison sentence for corruption [93]); Andrade Gutierrez [94] (which in May 2016 reached a US$ 286 million settlement in a plea deal with federal prosecutors for its alleged role in a massive corruption scandal involving oil company Petrobras); and real estate titan Carvalho Hosken (which was recently forgiven a municipal tax debt of R$ 7.6 million [95, 96]).

The consortium was gifted the land to develop the Olympic Park and will redevelop the site into luxury condos after the Games. In addition to tax breaks, the city also paid the consortium R$ 462 million for the Olympic development work, and contributed another R$ 8 billion in infrastructure to the area to enable the condo development. Furthermore, thanks to Rio's `exceptionality laws', devised specifically to fast-track Olympic development without public debate, the consortium has also been able to bypass a range of building codes and zoning restrictions. In turn, Odebrecht and real estate property tycoon Carlos Carvalho have made enormous campaign contributions to both the former Governor's and the Mayor's political war chests [97].

Documents uncovered in March 2016 allegedly show that Odebrecht executives are connected to R$ 1 million in suspected bribes that link to two Olympic legacy projects [98]. As a result, in May 2016, federal prosecutors announced an investigation of the city's Olympic legacy construction projects (it is the city government that oversees most Olympic construction projects). The investigations include a probe into the federal funds earmarked to build a series of sewerage treatment plants to clean up Rio's chronically polluted Guanabara Bay (a project which never transpired); an examination of the five construction firms that are responsible for building most of the R$ 39 billion in Olympic venues; the use of R$ 1.76 billion in federal funding for `legacy' infrastructure; the R$ 8 billion renovation of Rio's Porto Maravilha tourist area; and the expansion of the city's metro line connecting the main Olympic arena in Barra de Tijuca (another unfinished project with a 50% cost overrun). Most of these projects have violently forced the relocation of hundreds of low-income families, yet as Chris Gaffney commented to Dave Zirin in a recent article published by The Nation, “The Construction Industrial Complex of Brazil is similar to the Military Industrial Complex of the USA” [99]. As such, it is likely to weather any corruption probe. Even if the investigation directly links to misconduct involving elected officials, it is certain that its scope will not go so far as to include malfeasance by police [100].

Brazil's Construction Industrial Complex may be reaping in Olympic profits, but the country itself is suffering badly. Brazil's national budget deficit is expected to reach 12% of GDP for 2016, and its gross debt-to-GDP ratio (currently running at 70%) may rise to an incredible 85%. On a state level, Rio has already defaulted on two payments of external debt obligations to ADP (a French development bank) and the Inter-American Development Bank. The state's overall debt has reached 225% of net current revenues, to breach the 200% ceiling stipulated by Senate Resolution #40 (2001). As of April 2016, the state's deficit was amongst the highest in Brazil [101].

The city is not faring any better with the second highest debt ratio in the country. Mayor Paes claims he is confident the city can manage it, given the Fiscal Responsibility Act, which offers a debt ceiling of up to 120% of revenue (currently it is at 30%). However, in the last three years city revenues have decreased and unemployment and inflation are on the rise. In addition, immediately following the Olympics almost 30,000 construction workers will be out of jobs, and that is just one employment sector. Furthermore, repayments on the municipality’s US$1,045 billion World Bank loan (for urbanization and development) begin in 2017 [102]. Rio's financial collapse has strained a range of critical public services, including public security. Police helicopters have been grounded, patrol cars are without gasoline, police salaries are being withheld, and incident reports can’t be written because there is no paper to print them on, or printers left with ink. And there are a lot of incidents to report in the formal city, where street robberies have risen to an 11-year high [103]. Many police units are relying solely on donations of stationery, cleaning supplies, and toilet paper to remain functioning at all. At a civil police protest held at Rio's Galeão airport at the end of June, disgruntled officers greeted international arrivals with a banner that read “Welcome to Hell. Police and firefighters don't get paid—whoever comes to Rio de Janeiro will not be safe” [74]. The following day, mutilated body parts washed up on the beach in Copacabana near to the Olympic volleyball pavilion. The police continue to occupy Terminal 2 at Galeão and to march in protest along the main avenue leading to and from the airport.

The federal government, under Interim president Michel Temer, claims there is “a solid security program” in place for the Olympics. Soldiers, helicopters and naval vessels have been federally deployed to bolster security operations for the event (Figure 5), but state authorities continue to delay civil police salaries and scale back pacification ambitions. As the crisis deepens, publically aired malcontent between city and state leaders about how public security is being mismanaged continues to grow [103]. In a city of 12 million people where armed muggings, stray bullets, fatal car-jackings, and favela wars are escalating, and public servants no longer being paid, there is public anger at the R$ 2.9 billion emergency funds that have been redirected away from critical needs to service the Olympics, especially at a time when the Chief of Civil Police, Fernando Veloso, admits he “can't discard the possibility of a [security] collapse” because police are “at the limit of [their] operational capacity” [74].

Figure 5. Troops stationed in Copacabana for the Olympics.

8.- The Inter/National Security Framework

Brazil's federal interim government have orchestrated a series of international security actions that are coordinated through the Centre for International Police Cooperation (CCPI) as part of an `integrated system of command and control'. The operations are implemented by the Ministry of Justice and Citizenship’s Special Secretariat of Security for Major Events (Sesge). The CCPI and the Anti-terrorism Integrated Center (CIANT) is cooperating with Interpol, Europol, Ameripol, and 250 police representatives from 55 countries to provide Olympic security [104]. The efforts are led by federal police and headquartered in two command and control centers in Rio de Janeiro and Brasilia. They are fashioned after the FIFA Confederation (2013) and World Cup (2014) security operations which led to massive violations of human rights perpetrated by police [7]. The largest police operations focus on deploying integrated mobile teams of federal police and military units to secure areas in and around competition venues, many of them inside the favelas [105]. It is the largest international police cooperation action in the history of both Brazil and Interpol.

The vague language of `terrorism' as it appears in the legislation that supports these operations, suggests the military deployments will be focused on amplifying operations in the favelas and to crack down on public protests. Despite the range of security assurances offered, and the thousands of troops deployed, the security situation has continued to be plagued with problems. Weeks before the Olympics some security contracts for basic safety equipment had yet to be awarded. In April, Col. Moreira, commander of one of the key Olympic security forces—the National Force for Public Security–resigned his post without explanation [106]. Two weeks before the start of the Games, National Security Force troops charged with securing the main Olympic venue threatened to abandon their posts due to the poor conditions they have had to endure—living in government housing blocks with a lack of water, clogged sinks, leaking sewerage, without bathrooms, showers, or bed rooms, being fed rotten food in a neighborhood surrounded by favelas dominated by militias and traffickers [107].

9.- A Legacy of Corruption and Insecurity

Corruption, violence, and insecurity have always been pervasive in Brazil. The police's right to use violence, as sanctioned by the judiciary, in order to protect State interests is representative of just one aspect of this. The ongoing violence around the Olympic developments is only the most recent manifestation of political elites protecting their connections to private business interests.

In Rio, the police and the courts are the public institutions most directly involved in determining the seizure, control, and distribution of property rights. The Police—as the State's enforcing institution—has the strongest influence on determining the de facto ownership status over property. This is most obviously demonstrated in the questionable legality of Rio's seizure of favela territory and the mass evictions and `social cleansing' operations that have ensued. Control over land has had a direct impact on shaping police actions in relation to these land grabs. The violence with which they have occurred has undermined any informal (yet legitimate) property rights of the poor, without neutralizing the ongoing threat posed by the criminal actions of gangs.

The link between violence, economic inequality, political corruption and economic growth is a key and persistent theme across the city and state [108], with the police playing a pivotal role in the institutional nexus of the urbanization/development paradigm. In the favelas, police do not even have to claim that their victims are armed for them to justify extrajudicial killings. Due to inconsistencies in the public’s and the police's reporting of crime, it is impossible to quantify the full impact of police activities inside these communities in terms of human and social cost. However, it can be said that the state's semi-legal seizure and violent control of favela property for the Olympics has been a key determinant in generating enormous private, short-term economic profit from the city's urbanization and development agenda.

Violence occurs in Brazil to such a degree that it has become a societal norm. To put it in context, between 2004 and 2007, there were 23,000 more deaths by homicide in Brazil than deaths occurring through armed conflicts in Iraq, Sudan, Afghanistan, Columbia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sri Lanka, India, Somalia, Nepal, Pakistan, India, and the Israel/Palestinian territories combined [45]. Though homicide rates in Rio's favelas dropped between 2007 and 2012, they are again rising at an alarming rate. In Rio, one out of five homicides are attributable to police. The majority of those killed are poor, black youths living in favelas [65]. Sharp spikes in extra-judicial killings and rights violations perpetrated by police transpire exponentially during mega-events, and occur with impunity.

In economic terms, police violence costs the country the approximate equivalent of 1.2% of the country's GDP annually [109]. Security costs due to mega-events increase this number substantially. Despite years of political rhetoric that has espoused Rios pacification campaign as a cornerstone of Rio's Olympic legacy, and a promoter of sustainable economic growth, citizen participation, and good governance [14], it is clear that neither it, nor Rio's public security Games Plan in general, has done much to provide public security for the city.

Rather, Rio's militarism is part of a wider framework of `structural violence' that produces suffering—both directly through acts of violence, torture, and murder, and indirectly through an institutionalized political social pathology that results in dispossession, lack, and insecurity. Paul Farmer stresses these “offensives against human dignity” (2003: 8) are disproportionately perpetrated against the poor (2003: 50) and link to other invisible forms of structural violence that are produced by transnational political-economic processes (2003: 18) [110]—such as the Olympics. The interrelated profit-making goals of the economic elite, government, and the IOC, directly connect Rio's militarized violence to the flow of global capital. That is, the processes of exploitation and human rights abuses the police are enforcing on the ground are historically, institutionally and economically driven by the State, but attached to a privileged handful of government-backed private stakeholders that have been able to profit in the billions from Olympic development opportunities. It is a politico-economic arrangement crafted through a coalition of laws, policies, privatization, and policing, designed to maximize profiting-making. It amounts to what Mike Davis describes as “a form of low-intensity warfare” [111].

Police in Rio are accredited as being responsible for more than 5,000 civilians deaths in the years since the announcement of the winning the Olympic Games bid, accounting for 16% of homicides overall during this period. Those killed by police in revenge killings and summary executions include children as young as ten years old. Social media posts by police proudly boast that police “go into the favelas to kill” [7]. UPP and Special Ops troops run through the favelas daily with assault rifles drawn, pointed, and ready to fire. As an outsider working in favelas, I have experienced this myself many times. And it is terrifying. It is difficult to blame the police, who, from their perspective, could be shot at any time. It is the policy that is fundamentally flawed. Military pacification without community dialogue or social investment makes it impossible to build trust. As a result, institutionalized violence pushes people toward placing more trust in trafficking gangs and illegal militias than in State-sanctioned `law enforcement' [47].

The return of territory to the state is a necessary foundation for the improvement of Rio's public security, and if instituted alongside investments in social infrastructure, judicial reform, and without dispensation of impunity. Indeed, the UPP program—as an authentic form of community policing—could potentially have been used as an instrument to aid in the repair of social rights. The direct relationship between citizens and their territorial rights, both through legislation, and as embodied experience, could have been fundamental in creating the democratic right to the city for the people living in favelas. However, as it stands, the UPP is not a means with which peace or public security has been restored [112]. Nor has it delivered the promised legacy of a safe city for the Olympic Games [65]. Yet, as Mark Neocleous has pointed out, these goals have never been its objective [5, 113].

The flaws in Rio's security-driven logic and its militarized management of the favelas, and the flow of capital behind it, are apparent. Just a month before the Olympics, a 78% increase in the number of deaths from police actions (up from 47 deaths in February to 84 in May), means Rio's police are now killing one person every nine hours. AI has even launched an app. called Cross-Fire for people to use as a tool to “document gun violence in Rio ahead of the Olympics” and “to urge the authorities to take some real steps to tackle the crisis” [114]. It is part of AI's “Violence has no place in these Games!” campaign. In addition to the right to life, freedom of online expression is also being curtailed. On the first day of July, two men were arrested for publishing criticism of police on the Internet [115]. Police are also starting to test their ability to block cell phones during the Games [116].

Gunfire exchanges are a frequent occurrence both inside favelas and out. Ten shoot-outs on the city's highways have occurred since the beginning of the year, and in early June 2016, 25 armed gunmen stormed a city hospital in a shootout with police, in an attempt to free a drug trafficker. At the end of month, police raided a baile funk, killing six people and wounding more than thirty. And so it goes on. Tourists have been shot dead and robbed at gunpoint, and young girls have been gang raped. The current bodies responsible for the public security management of the city do not provide safety and freedom for the wide populations that are gravely threatened by its deficiencies. Additionally, the State security apparatus of pacification—that puts policing at the center of social order—has deliberately and intentionally sacrificed the people living in favelas, and their basic rights of citizenship, for the sake of Olympic development in service of the production of markets [117]. Vera Telles asserts that the hostile, militarized management of cities such as Rio uses security-driven logic to articulate strategies of power and further the production of markets [118]. These forms of violence and control inscribe themselves on the Olympic City as fields of tension and conflict.

10.- Discussion

Rio’s favela communities have continued to live under the crushing weight of discriminatory policing for decades. International watchdog advocates such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, continue to call for an end to the violence and an investigation of Brazil's policing and criminal justice systems. Local organizations, such as the Comitê Popular Copa & Olimpíadas Rio have focused on strategies that monitor and confront the exclusionary nature of urban policy (and its impact) in relation to the city’s mega sporting events—specifically the 2011 Military World Games, the 2013 Confederations Cup, the 2014 World Cup, and the 2016 Olympics. These organizations, and the communities they advocate for, demand meaningful oversight and accountability of law enforcement policy and procedures, and an end to the criminalization of communities of people of color who are living in poverty. They also call for government to invest in these communities by funding more than military police offensives.

Media attention is momentarily focused on Rio for the Games, but the anger and grief caused by the public killings of sons, daughters, fathers, mothers, sisters and brothers has yet to translate into policy reform. Elected state and municipal leaders fail to acknowledge any role corruption has played in the transformation of Rio into a mega-events city, or how this has exasperated the already endemic problem of police brutality and the criminalization of the poor in Rio's favelas.

Corruption, particularly inside developing contexts, diverts resources away from poverty-alleviation efforts and sustainable development. The average annual estimated cost of corruption in Brazil is between 1.38% to 2.3% of the country's total GDP—as much as US$53 billion annually [119]. In a situation where political corruption is as pervasive as this, it is difficult to propose effective ways in which police corruption can be mitigated. The core of the problem in Rio is that corruption permeates the political apparatus almost everywhere. Policy instruments in stable contexts can use public agency to improve conditions in the public realm. However, in the case of Rio, and Brazil in general, extensive corruption impedes any situation where regular policy thinking can be applied. Corruption is a crime that relies on the agencies of the police and the courts to rectify. When these systems are corrupt to such an extent as they are in Brazil, few in decision-making positions have the interest or capability to intervene in them effectively. In situations such as Rio, it is difficult to suggest concrete policy proposals, though some basic changes to legal tenants may be proposed to ease some of the problems.

A relaxation of Shock Orders—the stringent crackdown and regularization bureaucracy of illegal goods and/or services, including housing—should be considered so that informality is not stamped out just because it is informal. The partial deregulation of informal systems has proven to be helpful in reducing police corruption and stabilizing informal communities [120, 121].

Regarding drug trafficking, the US-led `war on drugs' has created so many inter-country trafficking spillovers that only international efforts may resolve the situation. In Rio, this war is currently framed through pacification policy. The results have been dismal. There has been no reduction in violence and corruption as generated by the drug industry, only a temporary relocation of traffickers to unpacified areas when necessary. Ex-Brazilian President, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, recommends breaking ties with this failed strategy—which relies on developing countries engaging in urban warfare and on the ground combat. Instead, it recommends re-focusing on efforts that target consumption and the personal and social damage caused by it, as well as policies that target organized crime and corruption. It goes on to state that the “imposed harmful policies” of the war on drugs “have had dire consequences—corruption of the police forces and judiciary and traffic-related violence” [122].

There is no large-scale production of drugs in Brazil (with the exception of marijuana). What exists is the territorial control of urban favelas by traffickers, who are supplied with cocaine from neighboring countries, and who distribute the majority of their supplies to a domestic market, more so than transiting them out of the country. Given the high rates of poverty and unemployment in favelas, the traffickers easily form extensive networks of dealers, distributors, and consumers. Rio's large consumer market is driven mostly by the middle- and upper-income classes. According to Cardoso, “as long as demand and profitability remain high, it will be difficult to withhold the attraction that trafficking carries to a young mass of people, including children, coming from the poorest populations…The police force, with some exceptions, is divided between those who assent to traffickers and those who enter the favelas to kill. To the mother of the often innocent victim, it makes no difference if the `stray bullet' left the gun of a criminal or a policeman” [122].

Increasing levels of education has yielded positive results in regards to reducing both micro and macro levels of corruption [123]. Increasing police wages may also prove effective in reducing corruption levels on a micro-scale, however, literature on the subject is ambiguous at best [124]. The open extortion by Rio's police is so visible and so pervasive that it should be possible to address directly. However, because of a compliant judiciary system, and a fear of police reprisal, the public-at-large remain extremely vulnerable to it. Incidents of extortion may be reduced by making arrest, detainment, and judiciary processes more rigorous and transparent. Granting stronger rights for suspects is also a step toward police accountability.

The widespread use of mobile phones and social media outlets has increased the ability for the poor to expose cases of police abuse, however, the use of social media in Brazil's current political climate itself carries the risk of arrest, detainment and a prison sentence. Despite the risks, social and independent media outlets remains one of the primary ways of exposing corruption and misconduct [7]. In addition, organizations such as AI continue to arm the public with tools such as their Cross-fire app. They and other organizations such as Comitê Popular, Mída Ninja, and Rio On Watch, continue to apply pressure on members and representatives of the Rio 2016 security commission, the military police, and the government, to take specific responsibility for security operations before and during the Olympics. AI, specifically, has called for the Rio 2016 security commission “to establish full accountability mechanisms for any human rights violations committed by law enforcement officers; to investigate and hold perpetrators to account; and to fully support and provide reparations for victims and their families” [125]. However, without a complete overhaul of the entire judiciary system, which currently fails to investigate or hold police accountable in the face of overwhelming evidence, few advances toward securing the right to life are likely to be achieved.

The lack of provision of basic social services and the generation of decent, living wage employment (and income) prospects for people living in favelas also presents a barrier to developing stability within these communities. Provision of social services and basic soft infrastructure is an important component of an effective response to poverty. Funding for the staffing and maintenance of social infrastructure facilities and their programming and services needs to be consistent if any progress is to be achieved. Currently services are often discontinued due to politically-motivated policy changes and budget cuts [126]. The city's persistent failure to provide stable social infrastructure services include its revolving 'community policing' policies [127]. Time and time again, these policies are abandoned, leaving residents to cope with the fallout [128]. The state's failure to deliver basic soft infrastructure services, coupled with the frequency of gross political and police misconduct, continue to reinforce negative perceptions of Rio's state interventions in the minds of favela residents.

How public assets, especially favela territories and the funds earmarked for providing infrastructure for them, are currently being appropriated is another issue that remains absent in political discourse. Until these policies are scrutinized in a public forum by inclusive means, there will be no asset recovery, certainly none that benefits Rio's informal sectors. This is a particularly important issue for fragile states such as Rio, where high-level corruption has recklessly misused, mismanaged, and/or misappropriated public funds, and where resources are badly needed for reconstruction and the rehabilitation of informal societal sectors.

Finally, corruption prevention measures must be directed at both the public and private sectors. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, preventive policies, such as the establishment of anticorruption bodies, enhanced transparency in the financing of election campaigns and political parties, and the safeguarding of public services, should be subjected to codes of conduct, financial and other disclosures, and appropriate disciplinary measures that promote transparency. Furthermore, accountability in matters of public finance must be promoted by setting up methods for preventing corruption in critical areas of the public sector such as the judiciary and public procurement. Further, it should include the involvement of third sector and community-based organizations, and other civil society watchdog and rights advocacy organizations [129].

11.- Conclusion

The social fabric of public space is considered critical in defining the right to the city [130]. Yet, the role that public security in informal space plays in strengthening or undermining the socio-economic stability of cities such as Rio is rarely valued. Instead, the public spaces of favelas are perceived of as arenas for contestation where people's already marginalized citizenship freedoms—restricted by poverty, ambiguous legal status, and systemic violence—need be controlled through unmonitored militarized action [130]. This lack of monitoring increases police violence, corruption, economic exploitation of the citizens, and abuse of the police’s role of protecting public space [120].

In Rio, government leaders operate inside a corrupt political economy in which pacification is only one component. It is part of a broader condition that is commonly referred to in Brazil as jeitinho—the way things are done for personal gain at the expense of, and detriment to others [131]. It is clear that the State needs to take steps to reduce the violence the city of Rio de Janeiro has seen over the past decades—some of the highest rates in the world. If Rio had followed through on the vision it lays out in its municipal master plan—one of sustainable development and the fulfillment of the social function of the city and of urban property [132]—pacification activities in favelas could have theoretically made strides in social development through participatory means. Unfortunately, gathering the political will to deliver on such a promise, in a country that is institutionally corrupt and relies on exerting lethal military force to maintain control over its citizens, remains unlikely.

Police violence, misconduct and institutionalized corruption are not the same issues in the formal city of Rio as they are in the favelas, where the separate public security policy of military pacification has far more lethal consequences. The outcomes are unequal, unfair and throw already stressed and socio-economically destabilized households into deeper levels of poverty and violence. The pacification policy is also responsible for the migration of crime, an increase in the rates of victim crimes, and the proliferation of a culture of police corruption that can be linked to organized crime, an increase in homicide rates, and the trafficking and consumption of illegal drugs, all of which are typical of the outcomes seen in other developing contexts [133].

The same bankrupt government agencies that have had a powerful influence over the crafting and management of Rio as an Olympic city are now looking at having to reconstruct a collapsed state, floundering in financial calamity and on the brink of a “total collapse in public security” [134]. The deteriorating situation caused by pacification has been described as “critical” [135]. After the Olympics a bloodbath is predicted as funds dry up even further, UPP units are further disbanded, and turf wars over gang control resurface as troops pull out.

Compounding the problem, Brazil as a nation has begun engaging in sweeping austerity measures that are hitting the country's poorest the hardest. In the favelas, internal de facto reconstruction may be the only way forward—where informal local actors will produce change once pacification dissolves. However, the prognosis is grim as the internal return of favelas to the pseudo-sovereign state of gang rule leaves residents with little democratic opportunity to successfully, or peacefully, reconstruct their communities.

Some third sector and government bodies may be able to marginally assist in post-pacification relief, but these organizations will be limited in terms of providing solutions. One thing is for certain, a range of post-pacification challenges are about to emerge in Rio's favelas, and no one, least of all the State, has a full understanding of their implications.

References

| [1] | Rio 2016TM strengthens ties with State Public Security Insti- tutions. Rio 2016 Olympic News. 2013 Apr 4; Available from: https://www.rio2016.com/en/news/rio-2016-strengthens-ties- with-state-public-security-institutions. |

| [2] | Unidade de Pol´ ıcia Pacificadora (UPP) Information Re- garding Pacified Territories. Governo do Rio de Janeiro Unidade de Pol´ ıcia Pacificadora website; Available from: http://www.upprj.com/index.php/informacao/informacao- selecionado/ficha-tecnica-upp-babilonia/Babil%C3%B4nia% 20%20%7C%20Chap%C3%A9u%20Mangueira. |

| [3] | Human Security at the United Nations. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs; 2013. Issue 9. Available from: https://docs.unocha.org. |

| [4] | Harvey D. The ‘new’ imperialism: Accumulation by dispossession. Socialist Register. 2004;40:63–87. |

| [5] | Neocleous M. War as peace, peace as pacification. Radical Philosophy. 2010;159:8–17. Available from: http://www.radicalphilosophy.com/wp- content/files mf/rp159 article1 waraspeacepeaceaspacification neocleous.pdf. |

| [6] | Robertson C. Analisando os Prˆ emios e Reconhecimento Interna- cional da Cidade Ol´ ımpica. Rio On Watch. 2016 May 5; Available from: http://www.rioonwatch.org.br/?p=19553. |

| [7] | Rekow L. Police, Protests, and Policy in Rio de Janeiro—Mega- Events, Networked Culture, and the Right to the City. In: Foth M, Brynskov M, Ojala T, editors. Citizen’s Right to the Digital City. Springer Science; 2015. pp. 119–135. doi:10.1007/978-981-287- 919-6 7. |

| [8] | Though it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss the very wide and complex set of public security actions, economic development activities and urbanization projects to which the pacification is tied, the UPP must still be acknowledged as being as a dynamic part of this much broader suite of interrelated, multi-tiered government interventions which have combined to have a dramatic impact on people living in favelas. |

| [9] | For in depth critiques of the UPP and/or its connection to the im- plementation of urbanization policy see Rio On Watch; Ignacio Cano; Esther Werling; Robson Rodrigues; Marcelo Baumann Bur- gos; James Freeman; Joseph da Silva; Robert Muggah; Mark Neocleous; Leticia Veloso; Frischtak and Mandel; Burgos, Almeida, Cavalcanti, Brum, and Amoroso; and Theresa Williamson. |

| [10] | This information has been primarily derived from qualitative field research undertaken by the author in the field inside pacified areas between November 2010 and June 2016. It has been cross refer- enced against publically available data sets (IBGE, IPP, FINCON, ISP) and enriched by conversations with various representatives from government agents (municipal undersecretaries, program and project managers), civil actors (civil society organizations, NGOs, individual residents), journalistic and human rights reports, and sources at Rio’s Olympic Committee. |

| [11] | Statistics have been retrieved from data released by the Instituto Pereira Passos (IPP; http://www.rio.rj.gov.br/web/ipp, Programa de Acelerac ¸ ˜ ao do Crescimento (PAC; http://www.pac.gov.br), Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estat´ ıstica (IBGE; http://www.ibge.gov.br/ english) and Instituto de Seguranc ¸a P´ ublica (ISP; www.isp.rj.gov.br). |

| [12] | State with an uppercase “S” in this context refers to multiple tiers (federal, state and municipal) government agencies acting in official capacity on behalf of institutional goals and interests. It can also be linked to its Marxist roots as articulated by Louis Althusser and co-authors in Reading Capital (see in particular the original French edition 1965); and by Antonio Gramsci, whose work in political theory and sociology studies deconstructs how states use cultural institu- tions to maintain power in capitalist societies. Conversely, state with a lower case “s” refers specifically to the state of Rio de Janeiro. |

| [13] | Rekow L. On Unstable Ground: Issues Involved in Greening Space in the Rocinha Favela of Rio De Janeiro. Journal of Human Security. 2016;12(1):52–73. doi:10.12924/johs2016.12010052. |

| [14] | de La Rocque E, Shelton-Zumpano P. The Sustainable Devel- opment Strategy of the Municipal Government of Rio de Janeiro. Washington, DC, USA: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars; 2014. Available from: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/ default/files/Paper LaRocqueandShelton-Zumpano 2014 0.pdf. |

| [15] | Hurrell F. Rio Favela Population Largest in Brazil. Rio Times. 2011 Dec 23; Available from: http://riotimesonline.com/brazil-news/rio- politics/rios-favela-population-largest-in-brazil/. |

| [16] | Lopes de Souza M. Social movements in the face of criminal power: The socio-political fragmentation of space and ‘micro-level warlords’ as challenges for emancipative urban struggles. City. 2009;13(1):26–52. |

| [17] | Dowdney L. Children of the Drug Trade: A Case Study of Children in Organised Armed Violence in Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil: 7 Letras; 2003. Available from: http://resourcecentre. savethechildren.se/sites/default/files/documents/3261.pdf. |

| [18] | ICRC Unit for Relations with Armed and Security Forces. The Law of Armed Conflict: Basic Knowledge. Geneva, Switzerland: International Committee of the Red Cross; 2002. Available from: https://www.icrc.org/eng/assets/files/other/law1 final.pdf. |

| [19] | Foley C. Pelo telefone: Rumors, truths and myths in the ‘pacification’ of the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. Humanitarian Action in Situations Other than War (HASOW). 2014 Mar; Available from: https://igarape. org.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Pelo-telefone-Rumors.pdf. |

| [20] | Perlman J. Favela Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio De Janeiro. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2010. |

| [21] | Madeira LM, Rodrigues AB. Novas bases para as pol´ ıticas p´ ublicas de seguranc ¸a no Brasil a partir das pr´ aticas do governo federal no per´ ıodo 2003–2011. Revista de Administrac ¸ ˜ ao P´ ublica. 2015;49:3– 22. doi:10.1590/0034-76121702. |

| [22] | Brazilian Federal Law 11.530/2007. Instituting National Program- ming for Public Security with Citizenship - PRONASCI and other measures. Available from: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil 03/ ato2007-2010/2007/Lei/L11530.htm. |

| [23] | Reuters News Agency. Brazil’s OGX, conglomerate headed by Eike Batista, files for bankruptcy. CNBC News. 2013 Oct 30; Available from: http://www.cnbc.com/id/101149627. |

| [24] | Soto, A and Blount J. Batista’s Brazilian iron-ore unit files bankruptcy petition. Reuters News. 2016 Oct 16; Avail- able from: http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/10/16/brazil-batista- bankruptcy-idUSL2N0SB04S20141016. |

| [25] | Hearst C. Batista Leaves UPP Partnership. Rio Times. 2013 Aug 12; Available from: http://riotimesonline.com/brazil-news/rio- politics/batista-leaves-upp-partnership-rio-de-janeiro/. |

| [26] | Rio de Janeiro’s State Law 42.787/2011. Available from: http: //arquivos.proderj.rj.gov.br/isp imagens/Uploads/DecretoSeseg42. 787Upp.pdf. |

| [27] | de Souza ER. Os donos do morro: Uma avaliac ¸ ˜ ao explorat´ oria do impacto das Unidades de Pol´ ıcia Pacificadora (UPPs) no Rio de Janeiro. Ciˆ encia & Sa´ ude Coletiva. 2015;20(12):3951–3952. doi:10.1590/1413-812320152012.22552015. |

| [28] | Barrionuevo A. In Rough Slum, Brazil’s Police Try Soft Touch. New York Times. 2010 Oct 11; Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/ 2010/10/11/world/americas/11brazil.html. |

| [29] | Bringing the state back into the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. World Bank. Sustainable Development Sector Management Unit Latin America and the Caribbean Region; 2012. |

| [30] | There are several schools of thought relating to informality. The Dualist perspective subscribes that informal activities have few con- nections to the formal economy, and that the sector operates as a separate, less-advantaged, or dual segment of the economy. Le- galists believe in a formal regulatory environment but acknowledge that formal commercial interests collude with government to bureau- cratize or legislate to their advantage, and argue that governments need to simplify bureaucratic procedures in order to incentivize informal enterprises to regularize their businesses, property and assets. Voluntarists charge that informal enterprises have an unfair advantage because of their avoidance of formal regulations, taxes, and other costs of production and services. They argue that informal enterprises should be brought into the formal regulatory framework in order to increase the tax base and profit margins of the public and private sectors. The informal sector can also be seen as ille- gal because it is involved in producing activities that are forbidden, unauthorized, or operate in non-compliance with regularization laws. At the core of these theories lies an opposition between the informal and formal. For more see: Rekow, L., Pacification & Mega-events 86 in Rio de Janeiro: Urbanization, Public Security & Accumulation by Dispossession, Journal of Human Security, 2016. Volume 12, Issue 1, Pages 4–34; Chen MA. The Informal Economy: Defini- tions,Theories and Policies. Manchester, UK: Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO); 2012. Working Paper No. 1; Guha-Khasnobis B, Kanbur R. Beyond: Formality and Informality. In: Guha-Khasnobis B, Kanbur R, editors. Linking the formal and informal economy: concepts and policies. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 2007. |

| [31] | Hendee TA. The Health of Pacification: A Review of the Pacifying Police Unit Program in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Stanford, CA, USA: Center for Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law, Stanford University; 2013. Available from: http://cddrl.fsi.stanford.edu/sites/ default/files/Thomas Hendee.pdf. |

| [32] | Letter to Governor Cabral on Police Violence. Human Rights Watch. 2012 Jun 14; Available from: http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/06/14/ brazil-letter-governor-cabral-police-violence. |

| [33] | Warren J. 2013 Task Force Report Violent Crime Reduction in Rio de Janeiro. Seattle, WA, USA: University of Washing- ton, Jackson School of International Studie; 2013. Available from: https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/bitstream/ handle/1773/22749/TFI2013text.pdf?sequence=2. |

| [34] | World Report 2014: Brazil. Human Rights Watch; 2014. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2014/country-chapters/brazil. |